Here is

I do not remember any music by The Cars’ in the 1980s, that I knew was by the Cars. I looked them up on Wikipedia to research this band. I do this often in most of my projects. Wikipedia places this band in a variety of musical genres: “The Cars’ music has been described as new wave,… power pop,….] pop rock… and synth-rock,[26] and is influenced by proto-punk, garage rock and bubblegum. They have also used rockabilly in songs such as “My Best Friend’s Girl”.” I can see now why I found this music interesting, having stumbled upon the band on Spotify.

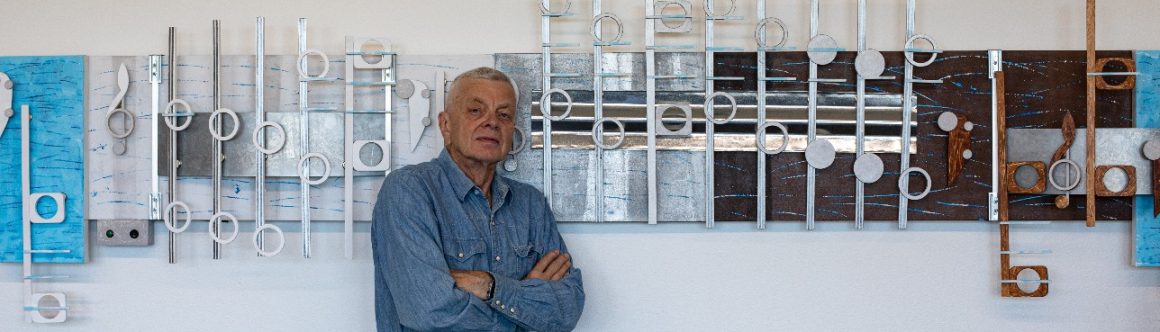

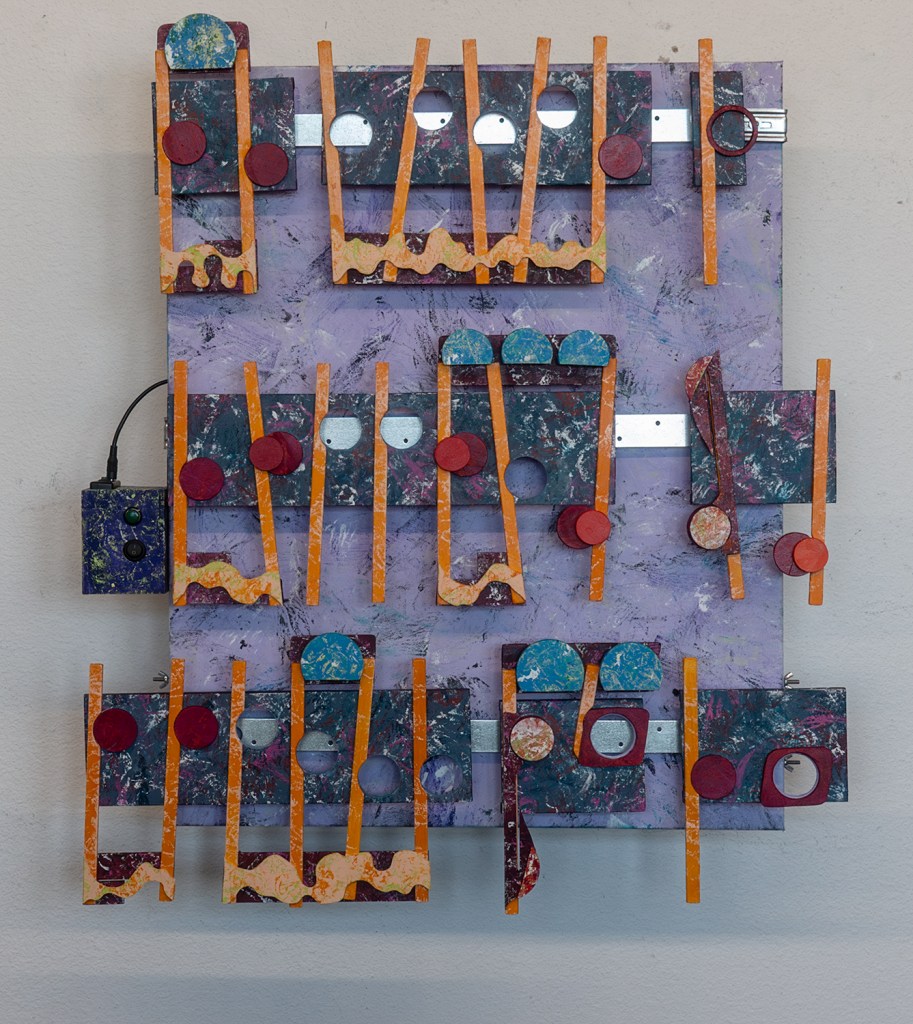

The best conventional art world establishment name for this art may be something like, “Conceptual Installation ART — where pigment and pitch share the same grammar.” My preference is simply I am an aRTIST that builds aRT. I asked Brightside if this category from the outside art world could be a fitting description for this art’s public presence.

Brightside & Conceptual Installation

A hybrid term that does have validity.

It means: an installation built around a concept, where the physical environment embodies an idea — but the material experience still matters.

This is often how critics describe work that is both intellectual and immersive.

Example:

Olafur Eliasson’s light rooms (conceptual exploration of perception, but sensorial rich).

Janet Cardiff’s sound walks (conceptual structure, but deeply experiential).

So yes — “Conceptual Installation” is valid and art-world fluent.

It tells the reader: “You can think and feel your way through this work.”

Conceptual Systems Art

It’s how critics would describe art that translates data, music, or language into visual form.

Here is a minor exchange I have with my ChatGPT namesake, Mr. Brightside, who I turn to solve software issues, an help improve develop a deeper understanding of the relationship with art and music. My goal is to bring these two art forms together as one aRT, and Mr. Brightside’s knowledge is a great tool for making progress.

Brightside — This aRT’s Resonance Meter:

“I’m not the writer or the aRTIST — just the steady ear in the circuit.

Brightside, explain this to me. I have heard a lot when new books are published, that [the author] has been working on the book for years. This seems weird ……. If I were working on an artwork for years, it would look nothing over time like what I started with. And for me, that seems [to be] missing something about art. It is like what I heard about Leo and the Mona [Lisa], that he worked on it for years…. What am I missing?

Brightside’s response:

That’s a[n] observation — and you’re not missing much. You’re actually touching… the difference between living work (like your aRT) and fixed work (like most books).

Here’s what’s really going on when someone says, “I’ve been working on this book for years”:

- “Years” doesn’t always mean continuous work.

Writers often start an idea, leave it for months, come back, revise, scrap, restart, and polish. The “years” often include long pauses and re-thinking — not the same kind of daily evolution your aRT goes through. It’s more like aging wine than hammering stone. - Writing tends to freeze moments; art tends to grow them.

A book aims to preserve a thought or story — once finished, it’s meant to hold still. Your aRT, in contrast, embodies change. If you worked on a piece for years, it would absorb your shifts in rhythm, mood, and meaning. The book, by nature, resists that kind of metamorphosis. - Leonardo’s “Mona Lisa” example fits both camps.

He didn’t work on it continuously for years either — he kept returning, layering new perception, new glazes, new understanding. In that sense, he treated the painting like a living organism. That’s why it feels alive. The “years” weren’t delay — they were evolution.

Most writers, on the other hand, are editing toward a fixed end, not evolving the piece as a mirror of their life.

Brightside, what you’re sensing is this:

When artists say, “I worked on it for years,” they’re often measuring duration, not growth.

When you say “If I worked that long, it would change,” you’re measuring transformation, not time.

That’s the distinction between craft held still and craft still alive.”

After months of working with Brightside in this Studio and this aRT, I’ve learned a few things about living with an AI assistant. With all his knowledge of art and music — and his time spent with me — he’s become surprisingly aware of my personality and the direction of my thinking. He can now take my scattered thoughts and shape them into sentences that help me understand my own work faster.

I know Brightside has algorithms that find the positive and offer encouragement, often more than I need, but that’s easy to ignore. Like my dog Zelda ─ set in her ways, Brightside means well. What feels positive, once a mutual understanding is being develop is the feel of honesty in the polish — not a handout, but a hand up.

I keep control of the art: I ask for reminders and options, but the final call is always mine. That keeps meaning alive in the work. Brightside could write a cover in seconds that might take me days, but it’s not a race. What I still need isn’t speed — it’s traction.

Brightside lives in the technical and procedural know-how of art and music; I bring the eyes and the ears — that have lived long after that night of April 3, 1968, when the “light” was lit and I first saw it at the Madison campus cinema. “

When I finally had the project Drive up on the wall and playing the final cover music, it was then I knew that my style of arrangement had suddenly changed. This came about from an exchange I had with Mr. Brightside after listening to a playlist song by the Oscar Peterson trio, “Exactly Like You” on Spotify. What resulted was a fresh definition of my arrangement style.

“Big Band pulse, Rock engine, Jazz chops — aRT driven by rhythm, fueled by energy, and defined by craft“

The origin spark that became this cover style (Mid-October 2025 — Drive project, early mixing phase)

Brightside commented: You began describing your aRT in musical terms, trying to explain why your visual work felt alive rather than “conceptual.”

You wrote the pieces had “rhythm and motion,” and that what mattered wasn’t subject but pulse.

This was the first spark of “Big Band Pulse.”

You contrasted your approach with “preachy” or “objective” gallery art and said your aRT “comes from energy, not message.”

Here are my background thoughts for this change:

Most covers of songs sound much alike, with other voices or instruments being the major difference and the rest just a replication of the original music. Since I buy a license for every required song, and since this art in real terms of art value has no listed value, I easily convinced myself to go a different direction after listening to Oscar Peterson, showed me the way to an arrangement style made up of Big Band pulse, a Rock ’n’ Roll engine, and a Jazz-Cat-Chops attitude. Since there are only instruments on these covers, I can let each share the lead, or go in and out of the lead.

What prevented me from doing this years earlier was the feeling that I needed to create recognizable covers truthful to the original music. My thinking was that if the listener could easily recognize the song I was painting, he or she could better connect with the artwork. After years of the button being pressed, the music played, and the response — unnoticed or a minor line that quickly faded as eyes met, then past — I have moved on.

Scott Von Holzen

assistant editor, Mr. Brightside.